Excerpt from the book "New Jersey State Troopers: Remembering the Fallen."

Chapter

Shootout with the Black Liberation Army

Werner Foerster #2608

It was a quiet start

to what would be a historic night for the New Jersey State Police. Troopers Robert

Palentchar #1946, James Harper #2108 and Werner Foerster #2608 were given their

assignments. Foerster had the northern area, Palentchar the southern portion and

Harper the middle. These men worked out of one of the three stations responsible

for providing services to the New Jersey Turnpike. Newark

and Moorestown are the other two. New Brunswick

While doing administrative work, Ron Foster was

startled when the radio sounded. Trooper Harper was calling in a motor vehicle stop—“an

early 1960 [white] Pontiac

Foerster observed Harper

talking with the front passenger and the driver standing in front of Harper’s troop

car. Harper had noted “a discrepancy in the registration” and had asked the driver

(later identified as Clark E. Squire) to step out of the car and move to the front

of his troop car. He spoke briefly with him before leaving to speak with the other

occupants of the vehicle. This is when Foerster pulled up. The front-seat passenger

told Harper that her name was Maureen Jones; however, her name was actually Joanne

Chesimard, the “revolutionary mother hen of the Black Liberation Army” (BLA). As

Harper spoke with Chesimard, Werner Foerster performed a protective pat-down on

Squire and found a loaded gun clip on him.

Apparently, as Foerster was performing the pat-down, Harper was noticing that Chesimard

kept her hand in her purse. Then, imprudently, Werner supposedly yelled to Harper

that he had found an ammo clip. With that utterance, Chesimard pulled out a loaded

semiautomatic handgun and shot Harper in the shoulder.

Under continuous fire

from her weapon, and after being struck, Harper managed to draw his weapon and return

fire while tactically retreating toward his troop car. A vicious firefight got underway,

with Werner Foerster and Clark Squire fighting in the middle. Chesimard exited her

vehicle with gun blazing, as did the back-seat passenger, James F. Coston. He, too,

had a weapon. As the two exited their car, Harper shot at both, dropping Chesimard

to the ground and striking Coston with what was to be a mortal wound. Despite being

shot and on the ground, the BLA leader continued to shoot and turned her attention

to Foerster, hitting him in the chest and the right arm. Harper had exhausted his

rounds from his inferior six-shot revolver and was forced to retreat toward the

state police station.[iii]

Alone, lying on the

ground, Foerster was executed with two bullets to the back of his head. Supposedly,

Chesimard is the one who pulled the trigger.[iv]

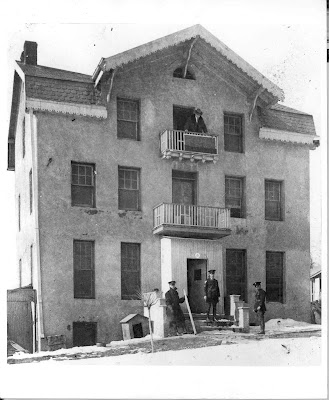

Location of Shootout

(c) 2010 John E. O'Rourke

As the BLA members drove

south, Harper—apparently in shock—walked calmly into the station (leaving Ron Foster

to believe that Harper had cleared from his motor vehicle stop). Foster said, “Jimmy

comes into the station and says, ‘Ron, you better put more troops out there; those

people have guns.’” Foster laughed, thinking that Harper was taking a crack at the

lack of a police presence on the road that night. “Jimmy,” Ron replied, “all those

people out there now carry guns.” However, Harper’s response was, “Yeah, but they

just shot me.” Turning, James Harper showed his bleeding bullet wound to his colleague.

At no time did Harper mention Werner Foerster being out with him. Presumably, Harper

assumed that Foerster had called out with him. However, he did not, leaving everyone

to assume that Foerster was out on patrol. (Regardless, a quick response would have

been futile in light of the coldblooded execution.)[v]

Working

on information that Harper had initially called in, Trooper Palentchar found the

car, with Clark Squire standing near the vehicle at milepost 78 south. Seeing the

trooper, Squire fled into the woods, with Palentchar firing a round at him. Then,

out of the corner of his eye, Palentchar saw Chesimard walking with her hands in

the air. A closer inspection of the woman revealed that she was seriously wounded.

Discovered a short distance from her was the body of James Coston.[vi]

In the aftermath, much

was written of the shooting and of Joanne Chesimard. Justice was swift for James

Coston. For Clark Squire, his punishment was life behind bars. Joanne Chesimard

received the same sentence, and she was sent away. However, state officials failed

to see the threat that Chesimard and her BLA associates posed, and she was placed

in the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women. In November 1979, a group of radical

domestic terrorists took two prison guards hostage and broke Chesimard out of the

minimum-security facility. Subsequently, Chesimard fled to Cuba

In all the words written about the shooting, little

has been recorded about Werner Foerster, a Jersey

trooper, husband and father. Unfortunately, this is to remain. The trauma of losing

Werner is still fresh in the memory of his wife, Rosa. As such, she did not want

to speak about or provide any information about her husband. A look into the state

police files isn’t helpful, either. Let’s explore what is known of the man.[viii]

Werner Foerster became

a Jersey trooper late in life—a life begun far from the Jersey Shores, in the city

of Leipzig in the German state of Saxony . The future trooper was born on August 19, 1938. At

the time, Germany Germany ’s military might was being carefully watched

by the United States Germany before

immigrating to America

Foerster was educated through high school. As

a man, he stood five feet, eight and a half inches tall and weighed less than 160 pounds. He had blond hair, blue eyes, a fair complexion

and spoke with a German accent. In December 1963, Werner entered the United States

Army and served in Vietnam

On November 18, 1964,

at the age of twenty-six, Foerster married a German woman named Rosa Charlotte Heider.

In December 1965, Foerster concluded his military service. He and Rosa moved to

Marboro Road Old Bridge , New Jersey New Brunswick Rosa became pregnant. On September 22, 1969, the couple’s

only child, Eric, was born.[xi]

On April 20, 1970, sixty-two

people entered training for the eighty-second

state police class; fourteen weeks later, on July 24, forty men stood as troopers.

The German-speaking former welder bore badge #2608.[xii]

Monday, July 27, was

Werner Foerster’s first day working as a trooper. His first assignment was at the

Toms River Station. During the next two years, Foerster worked out of the Colts

Neck, Fort Dix

A week before

Thanksgiving 1972, Foerster began patrolling

the New Jersey Turnpike. Only a few months stood between him and his encounter with

the Black Liberation Army.

All material and photographs are copyrighted and cannot be used without permission.

[ii].

Ibid.

[iii].

Ibid.; Werner Foerster Certificate of Death ;

Wikipedia, “Assata Shakur,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assata_Shakur#cite_note-36.

[iv].

Ibid.

[v].

Interview with Ronald Foster #2240; Werner Foerster Certificate of Death.

[vi].

NJSP Investigative Report H207396, May 14, 1973.

[vii].

New Jersey State Police, www.njsp.org; Lincoln Star, March 26, 1977; Post-Standard, March 26, 1977.

[viii].

Contact was made with Rosa Foerster by this author. Unfortunately, she didn’t

want to speak about her husband and advised that her son wouldn’t want to speak

on the subject either.

[ix].

Survivors of the Triangle website.

[x]. NJSP Museum

[xi].

Ibid.

[xii].

NJSP Personnel Order No. 62, April 20, 1970; NJSP Personnel Order No. 109, July

6, 1970.

[xiii].

NJSP Museum