Robert E. Coyle #238

Robert E. Coyle was born in the bustling, historic city

of Philadelphia on May 31, 1898. Raised in Philly, Coyle was of Irish heritage,

originating from the counties of either Donegal, Tyrone or North Connacht. The

Coyles were Catholic and gave their son a parochial education. Young Robert graduated

from St. Stephen’s Grammar School in Philadelphia. As he grew, Coyle gained

great physical ability. The world was at war, and Robert decided to enlist in

the United States Army. He served three years during the World War, but nothing is known of his service

other than that he was a private.

After his discharge, Coyle worked as a chauffeur in

Philadelphia. In the early twentieth century, a chauffeur was a prestigious job

that came with a great deal of responsibility. State police records indicate

that Coyle worked for two years with the Pennsylvania State Police; however,

the Pennsylvania State Police couldn’t confirm this.

Robert Coyle was invited to attend the eighth state

police class, along with Herman Gloor #240. Only two badge numbers apart, side

by side, Coyle and Gloor sweated through weeks of difficult training. His

experience driving through the busy streets of Philadelphia paid off for Coyle,

as he

proved to be an excellent driver.

On April 1, 1924, Bob Coyle was given badge #238. Bob

Coyle’s tour with the “outfit” would be brief, as the tragic day that would

take his life was only eight months away.

The increasing criminal activity attributed to

Prohibition was rearing its ugly head all over the country, and New Jersey was

no exception. The Roaring Twenties were a difficult time in America. The

phrase, coined because of the cultural movements taking place, could also be

used to illustrate the turbulent events taking place between law enforcement,

rumrunners and gangsters. An illustration of this is that on the day Coyle was

murdered, gangsters pulled an armed robbery in Bloomfield, New Jersey, and

troopers in New York shot and killed a rumrunner.

The last page in Coyle’s life is marked Thursday,

December 18, 1924. Troopers John Gregovesir and Robert Coyle were supervising a

payroll transaction for the Bound Brook Crushed Stone Company, which was a major

quarry nestled in the woods of Somerset County that employed a large portion of

the local population. Gregovesir and Coyle were sent to assist with the payroll

distribution. The manager of the company, Charles Higgins, went once a week to

the local bank, picked up about $6,000 in payroll money and delivered it using

Chimney Rock Road. One day, two suspicious men wearing long army overcoats

stopped Higgins, identified themselves as troopers and promptly questioned him.

Afterward, Higgins asked for police assistance and designed a plan that

would involve the New Jersey State Police. The plan was simple: the

superintendent of the company, William Haelig, would pick up the proceeds and

bring them to Higgins’s house, where Higgins, escorted by the troopers, would

deliver the money using an alternate route. Haelig took the usual payroll

route, serving as a decoy. Higgins’s plot worked, protecting the money and

foiling the robbery.

Higgins, Gregovesir and Coyle arrived at the quarry, and

the payroll was delivered without incident. Little did anyone know of the

danger lurking on Chimney Rock Road, as Haelig was stopped near the quarry by

two thugs posing as state troopers who inquired about the money.20 Haelig

returned to the quarry and told Gregovesir and Coyle what had happened, and the

two raced down the long quarry driveway and turned onto Chimney Rock Road in

pursuit of the bandits.

Traveling down the winding road—known today as Thompson

Road—the troopers spotted a man fitting the description. Unbeknownst to the

troopers, they were speaking with Daniel Genese, a hardened criminal who was a consummate

professional—calm, cool and collected. He made a career of robbing people.

Gregovesir and Coyle also noticed another man standing up at Dr. Donahue Lane

(today called Donahue Lane). The troopers thought it wise to question the two

together and, according to Gregovesir, drove Genese up to the intersection.

Whether the troopers searched the man isn’t certain. What is certain is that

Genese had a gun.

Genese was put in the back seat. Coyle went to sit

alongside him and was instantly met with Genese shouting, “Stick um up.” When

Bob Coyle looked up, a gun was in

his face. Coyle pulled his weapon, and Genese shot Coyle in the face. The gun

was loaded with blanks but burned Coyle’s face, giving Genese the chance to

grab the trooper’s gun. Genese then shot Bob Coyle with his own weapon. Coyle

fell mortally wounded. While this was transpiring, Gregovesir pulled his gun,

but was slow in doing so, and the seasoned criminal grabbed it. A round rang

out, missing both men. Within the small confines of an automobile, one trooper

was dead and the other was fighting for his life.

While Genese’s partner, John Anderson, a petty criminal,

was running to help, Genese won the struggle and took possession of

Gregovesir’s gun. Genese later said that he could have killed Gregovesir “but

didn’t want the blood of both of them on [his] hands.”

The state police had just marked the one-year anniversary

of William Marshall’s death and now was faced with another death. The state

police would stop at nothing to find the culprits. The senseless murder of

Coyle made troopers apprehensive, for the realities of the newly formed

organization were settling in. Leads came in as local residents reported seeing

two suspicious men a few days before the murder operating a red sports-type

vehicle. Colonel Schwarzkopf, in an interview, “tolled off on his fingers…the

reasons he believed” those committing the crime were “professionals of some

experience.” Schwarzkopf said the gun used was loaded with two blanks, “an old

gunman’s trick.” The weapon was neatly and conveniently concealed but readily

available. Schwarzkopf elaborated further: “The bandits had successfully palmed

themselves off as state troopers while gathering information about the pay

roll; that the bandit was case-hardened enough to shoot immediately without

compunction when the occasion arose.”

The investigation followed like a Hollywood movie; there

was a multistate manhunt, and police from all over took part in varying

degrees. State Police Captain Robert Hamilton set up a command post at

Pluckemin. Hamilton had risen through the ranks rapidly and, with about two

years of tenure, was commanding Troop B. The next day, the newspaper headline

read: “Trooper Slain by Captive;

One Death in Hunt.” Local residents were asked to help in

the search, and William Morton, a local auto mechanic from New Brunswick,

volunteered and rode sidesaddle in Trooper Harry Linderman’s motorcycle.

Linderman and Morton had been out all night combing the area when they were met

with an accident. The mechanic was catapulted to his death. Morton left behind

a wife and a young daughter.

Then, suddenly, there was a break in the case when a

local taxicab driver said that he had driven two individuals over the past

several weeks up to the Chimney Rock Road area. The taxi driver said that the

men spoke of two brothers from Hudson County, one of whom was called “Rags

Reilly.”

In his frenzy to escape, Genese had left his revolver at

the crime scene, and the gun proved to be unique. There were only five hundred

manufactured due to an infringement of patent.

The weapon Genese had left behind couldn’t be

traced back to its origins, but it was believed to have been shipped to Paterson, New Jersey, by the manufacturer. However,

records showed that it was never received. Presumably, some shady employee had

traded the weapon on the black market.

With only three years in existence, the state police

could not have fathomed that it would be challenged with managing a complex,

coordinated criminal investigation with state and local authorities involving a

murder of one of its own. Efforts were now being focused in Hudson County. In

light of the complexity of

the investigation, two seasoned Jersey City Police Department officers were

called upon. Lieutenants Charles Wilson and Harry Walsh were brought on board

and proved to be excellent cops, bringing the investigation to a successful

conclusion.

The handgun that Genese had left behind was processed for

prints by the two-month-old State Police Fingerprint Bureau. “Rags Reilly” was

found to be a convicted murderer doing a life term in prison. Investigators

focused on Reilly’s associates and thumbed through “25,000 photos along with Gregovesir.”

Genese’s photo was easily identified by Gregovesir. How could he forget the man

who had let him live? “He had a murderous look…I’ll never forget it,”

Gregovesir remembered. Three other taxi drivers came forward saying they too

had driven Genese up to the Chimney Rock Road area.

Investigators discovered that the red car Genese and

Anderson had used was in the hills near Stirling, New Jersey. Authorities

learned that Genese and Anderson had stolen a blue coupe and abandoned it in a

garage at 127 East Second Street in Plainfield about 3:30 p.m. on the afternoon

of the murder. From there, they picked up the red sports car they had hidden in

a different garage and proceeded up to Chimney Rock. In the weeks following the

crime, the red sports car came to be called the “murder car.”

Lieutenants Wilson and Walsh followed Genese’s trail by

searching the vital statistics registry and discovered that Genese had applied

for and obtained a marriage license in New York in 1923. The record indicated that

he had married a woman named Florence Kleffer. Kleffer lived at 172 Hopkins

Avenue in Jersey City. Upon checking the Hopkins address, detectives discovered

that Florence’s mother had remarried and her last name was now Berberich. This

led them to East Sixth Street in Plainfield, New Jersey, where they posed as

census takers. Under this guise, it was learned that Florence was living with

her married sister, Mrs. Paldino, at Mount Horob, which was close to the crime

scene.

Troopers stood vigil, waiting out in the bitter February

cold around the Paldino home. The discipline that Schwarzkopf had envisioned

for his troopers was now evident in their actions. Troopers went without sleep,

food and shelter and refused to abandon their posts. Every trooper involved wanted

to be there when the cold-blooded killer showed up. The credo of honor, duty

and fidelity was being adhered to.35

On the afternoon of Friday, February 8, Daniel Genese was

spotted entering the Paldino home. Troopers apprehended Genese inside the

residence, and the brutal killer turned out to be unarmed and gave up without a

struggle.

The exhaustive manhunt was over. The very next day, John

Anderson was arrested in Jersey City.36 Genese was interrogated and confessed

when he was told his prints were on the handgun he had left behind.

For their hard work and effort, Lieutenants Wilson and

Walsh were awarded the Distinguished Service Medal from the New Jersey State

Police. Seven years later, the state police would once again call upon Harry

Walsh’s expertise to assist with the Lindbergh kidnapping.

On December 15, 1925, less than a year after the murder,

Daniel Genese was put to death via electrocution. He asserted to the last

minute that he didn’t get a fair trial. Prior to his execution, his wife, two

children, mother, brother and sister visited him. Genese remained calm,

composed and fearless up to his last breath. The killer bent down, said an act

of contrition with two priests and then was strapped to the chair, where volts

of electricity soared through his body. It took three soars of electricity to

kill him. John Anderson escaped this fate by receiving a lesser sentence.

Robert E. Coyle’s funeral took place on December 22,

1924, at St. Veronica’s Church on Tiosa Street in Philadelphia. Bob Coyle was

twenty six years old.

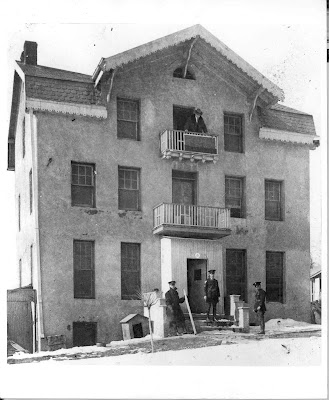

Then

(c) 2010 John E. O'Rourke

Now

(c) 2010 John E. O'Rourke

Courtesy New Jersey State Police

All material and photographs are copyrighted and cannot be used without permission.